I normally do not post about things outside of the time frame of 1600-1763, however, the Old Stone House of Buffalo New York could use our support. I am asking if all of you could help reach our goal of 12 letters of support to landmark the building. The hearing date is this Tuesday! And the best part is that the city is accepting letters via email ! We have literally 24 hours to make this happen, please help.

Thank you more than you could ever know, Tara

Letter of Support:

Cut and paste - The following letter to the Legislation Committee to show support for landmarking the Shcenck House. This one or one in your own words would go along way to show support. Our goal is 12 letters. We have only 2 days to accomplish this goal before the application is processed and they decide to decline or approve it.

Email: chawley@city-buffalo.com.

Dear Legislation Committee,

Please approve the request for landmarking the Schenck House, which was built by a father and son team in 1822. The Schencks were pioneers and understood the value of traditional farming methods that were in sync with the environment. They were a family that believed in "share and share alike" whether the child was male or female as recorded in their wills. The little brick summer kitchen is the site of the oldest surviving apple butter, cider and hard cider mill in western New York and happens to have been ran by a woman. They are role models that modern people can relate to.

Sincerely,

Here is the link to the Schenck House wiki page that I wrote and an article I wrote about it on Buffalo rising.com.

Dear Readers of Buffalo Rising,

The view from the front porch is through towering trees out across acres of lawn where at the horizon the sun is setting with magenta illuminating the sky. The oaks and maples frame the perfectly kept grass, where local golfers have plays for over a hundred years. The Schenck house has stood here watching over its golfers, and providing loving reminder of our past. Few people have noticed the two story stone house sitting in the middle of the park except the locals, many wondering just how old the place is. Golf carts buzz by, but one stops, “Are you here to save the old stone house?” My colleagues and I smile, “We’re going to try.”

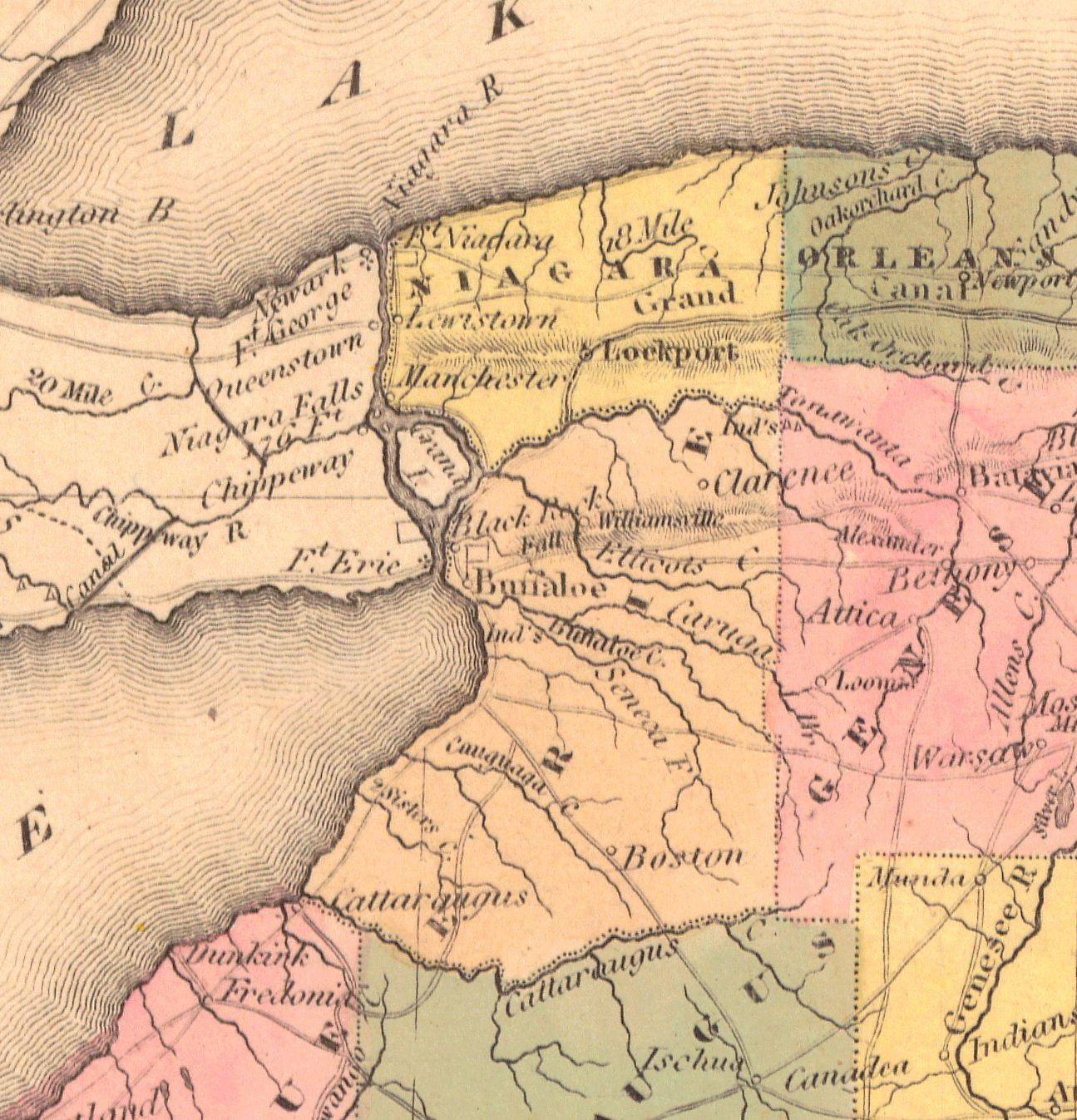

The City of Buffalo was only a village and the hamlet of Snyder a couple of farms when the Schencks loaded all their belongings into two conestoga wagons. They first arrived in America between 1702 and 1709 and lived for a 100 years in Pennsylvania farming their land in the traditional ways of the Germans; but with the opening up of new land for sale in Western New York they were packed and ready to make their way to their new home. With Michale and Catherine Schenck steering a team of four horses and a water tight Conestoga wagon of young children and their eldest son Samuel and his wife Sarah the other, they set out across the Allegheny Mountains in 1821.

“Michael Schenck emigrated from Pennsylvania in August 1821 with his family in two large covered wagons, drawn by four horses, came by way of Pittsburgh, over the mountain to Erie, thence to a point then called Comstock’s, eight miles from Buffalo, where he was compelled to place eight horses to one wagon, in order to get to Buffalo on account of bad roads, he settled in Amherst, and purchased one-half section of land at fifteen dollars per acre, near Snyder post-office, then heavy timber land.” [10]

Buffalo was growing quickly and by the 1850s its boarder was rubbing against the Hamlet of Snyder and the Schenck’s farm. According to one early source: Timothy Dwight – a traveler in 1804 states the following, “The only villages, which it contains, are Batavia and ‘Buffaloe creek’… Within the [indigenous persons] reservation is included the ground, opposite to Black Rock;… ‘Buffaloe creek’, otherwise called New Amsterdam, is built on the North-Eastern border of a considerable mill-stream, which bears the same name… The village is built half a mile from the mouth of the creek; and consists of about twenty indifferent houses…We saw about as many Indians in this village, as white people… [Since our journey in 1804 ] The ‘village of Buffaloe’ was burned down during the late war. Since that period it has been re-built, and is now a beautiful and flourishing town of one hundred and fifty houses.” Dwight’s observation were published in 1820, a sequel to this publication was expanded with additional information in 1822, “Beyond this hamlet a handsome point stretches to the South-west; and furnished an imperfect shelter to the vessels, employed in the commerce of the lake. Seven of the vessels, (five schooners, a sloop and a pettiaugre) lay in the harbor at this time.” [11]

Buffalo was growing quickly and by the 1850s its boarder was rubbing against the Hamlet of Snyder and the Schenck’s farm. According to one early source: Timothy Dwight – a traveler in 1804 states the following, “The only villages, which it contains, are Batavia and ‘Buffaloe creek’… Within the [indigenous persons] reservation is included the ground, opposite to Black Rock;… ‘Buffaloe creek’, otherwise called New Amsterdam, is built on the North-Eastern border of a considerable mill-stream, which bears the same name… The village is built half a mile from the mouth of the creek; and consists of about twenty indifferent houses…We saw about as many Indians in this village, as white people… [Since our journey in 1804 ] The ‘village of Buffaloe’ was burned down during the late war. Since that period it has been re-built, and is now a beautiful and flourishing town of one hundred and fifty houses.” Dwight’s observation were published in 1820, a sequel to this publication was expanded with additional information in 1822, “Beyond this hamlet a handsome point stretches to the South-west; and furnished an imperfect shelter to the vessels, employed in the commerce of the lake. Seven of the vessels, (five schooners, a sloop and a pettiaugre) lay in the harbor at this time.” [11]

Much of the history that is written for Buffalo tends to focus on the Victorian era, with a portion detailing Olmsted’s work from the 1860s and 1870s. Very little is talked about how “Buffaloe creek” came to be, what it looked like, or how people lived. We have a good sampling of 1830-1860s buildings; Little Summer St. can boast a number of 1830s and 40s homes, the Hadley stone farmhouse is in the Greece Revival fashion dating to post-1830, the Macedonia Baptist Church from 1845 and a few others give us a basic template to build visuals. However, as of today there are only two houses that date from a time when our 5th President James Monroe (1817–1825) was in office; the Coit House 1818 and the Schenck House 1822.

What is rather exceptional about the preservation of these two houses is that the Coit House is in the Federal Style influenced by British- American fashions and the Schenck House is in a European-American style called “Continental Pennsylvania German House” (CPGH or Continental). The Federal and Continental styles have a number of distinguishing factors with the Federal revolving around fashion and a sense of balance seen from the outside and the Continental Pennsylvanian eschewing fashion for practicality on the inside.

The Federal style has a central entrance door leading into a foyer with a floor plan of four rooms over four. Wheres, the Continental style was designed with central heating in mind, as Germans had developed the cast iron heating furnace and stove during the middle ages. With having imported their technology with them to America the houses continued to be centered on the stoves. The houses were arranged with three rooms over three, which off set the front entrance door to one side. The inventory from the 1840s for the Schencks lists a 10-plate stove with pipe in among several other items, a later inventory lists a new coal stove. However, the Schencks did not cook on their plate stove, it was a heater, they cooked out of their fireplace and pot chains are found in their inventory. Most interestingly, the walls of the house are three feet thick in the cellar, and two feet thick at the first floor tapering to the attic. For the Schencks, they were building to last centuries. Unfortunately, after only one year in their new home; first Sarah in the spring, then their two and three year old children passed, leaving Samuel alone.

Its never a good idea to leave a widow rambling alone around a big stone house. It appears that one pastor spoke with another and the following year Samuel married Magdalena “Lena”; who lived just the other side of the lake in Canada. Canadians, according to the early census records were as enthusiastic as the Pennsylvanian Germans to move to Buffalo and Snyder. The Town of Amherst had 1,556 Germans and 364 Pennsylvanians arrive by the year 1850, or 43% of the total population. The City of Buffalo had 9,409 Germans, 69 Prussians and 376 Pennsylvanians by 1850, or 23% of the population. On top of this were a conservable number of Canadians and French people. Each census cycle, the Schencks are recorded as having German laborers working on the farm, and were likely bi-lingual. There has not been any evidence of them ever having owned slaves.

The Schencks were unusual for other reasons too. Being of Continental European heritage, they not only loved central heating, they also brought with them a few other ideas thought both strange and marvelous to British- Americans. These unusual practices included; crop rotation, using manure as a fertilizer, letting land lay fallow to regenerate and the building of structures called barns. The English on-lookers were more amazed when they discovered that these immigrants built these massive barns to house their animals through the winter and even took time to grow hay and feed the animals during the cold months. This system of farming had developed during the later half of the middle ages; served the central Europeans well enough that the methodology persisted and was brought to America.

“…the Germans differed from practically all other Pennsylvania farmers, with the exception of the few Dutch, in providing shelter for their animals in winter. A traveler of the mid-eighteenth century noted shortly after his arrival in Pennsylvania that cattle around Philadelphia were neither housed in winter nor tended in the fields; after having been in the country for some time, however, he remarked that while the English and Swedes had no stables, the Germans and Dutch had “preserved the custom of their country, and generally kept their cattle in barns during the winter….They kept their animals as warm as possible in winter, and thereby effected considerable savings in hay and grain, for they found that cold animals eat more than warm ones…. the Germans began to build large barns rather than houses. The attention paid by Germans to the construction of barns, which became the envy of the non-German countryside, was brought out by one observer of 1753, who commented that “It is pretty to behold our back-settlements, where the barns are large as pallaces, while the owners live in log hutts; a sign tho’ of thriving farmers….The vegetable gardens were filled with weeds, intermingled with cabbages, turnips, and other plants.” German Agriculture in Pennsylvania, 1959, page 197 [27]

While the Schenck’s lifestyle is easily visualized in part because of their early adoption of technology and their tendency to stick with (what we modern thinkers might call) environmentally friendly practices despite the growing tendency to adopt synthetic fertilizers and specialization; but because, in the Schenck House, the ladies were viewed as partners. The women were producing small batches of products for market including; apple butter, dairy butter, honey and barrels of “graag”. “Graag” is hard cider. It is possibly the only 19th century example in the City of Buffalo where the original site and records survive for a female entrepreneur.

The property was first purchased by the Country Club of Buffalo who installed both a polo field and 18 hole golf course. Then resold to the City of Buffalo in 1927; where on the 1928 survey map we can see how the City promptly drew a bump out to include the farm and 18 hole golf course within the limits. The City renamed the property Grover Cleveland Park and Golf Course. In the 1970s and due to budget constraints, the City turned over the management – while retaining the property title – to Eire County. With ownership in the hands of the City and maintenance and Management in the County’s the Schenck house has survived in part because of the golf course.

The Friends of Schenck House support Erie County and the 2003 Master Plan to restore the oldest stone house in the City of Buffalo. According to the Master Plan, “Another notable heritage aspect of the Grover Cleveland Golf Course is that the site has one of the oldest stone buildings in Erie County on it, possibly dating back as early as the 1810s. [The 1810 cottage no longer exists] This structure is currently used for limited offices and storage for the golf course operations, and is in need of upgrades to preserve its structural and architectural integrity.” and “Actions prescribed by the 2003 Erie County Master Plan…Consider the inclusion of the stone house and outbuildings on the National Register of Historic Places. Consider a public/private partnership in restoring the old stone house structure and associated out-buildings. Potential exists for a heritage- related museum, restaurant, upgraded golf course-related facility, meeting rooms, etc. Maximize the access and visibility to Main Street, the proximity to the University at Buffalo and the close proximity to some of the region’s most prestigious homes as major marketing advantages for future uses at this facility.”

Our goal is to get Landmark status, replace the roof which is leaking, complete a restoration plan… and eventually get to the point where 1) the University of Buffalo’s Departments of Anthropology and Architecture can hold field classes on site 2) baking classes can be made available to the public 3) and for all the local brew and drink lovers out there… bring back Lena’s “graag” and install a still. (I’m thinking October Fest !) In this we would put into adaptive re-use a city owned house for the public events and generate on-going cash flow for maintenance of the site. If you are interested in being involved please message us through Facebook. We are looking for people with a variety of talents to lend a hand in bringing back a bit of our history for public use.

Thank you, The Friends of Schenck House Est. 1822