They turn up in both Dutch New Netherland and British New York. Except, they are not historically called pirate or cavalier dresses. On the Continent and in early American inventories this type of gown is called a Tabbaard. Common spellings: Tabbaard, Tabbard, Tabbart, Tabbert, Tabb...etc. The key to a good replica of a tabbaard - as compared to the costumes in movies - is a snug fitted bodice that compresses the bust not the waist and looks like it is mounted on pasteboard; with a skirt with many tiny pleats. The best part is... they are fair game for reenactors and historic sites.

The tabbaard is one of those dresses that is representative of people from a wide range of economic backgrounds. Whether your were a farmer in the town of Beverwijk - now the City of Albany, NY - the wife of a small town doctor on the Hudson River... or even the Electress of the Holy Roman Empire in Europe; the tabbaard was a gown accessible to people of various classes. It is reflective of the landscape these early Americans lived; where, while not royals, with industry and good provenance one could have a splendid gown of silk for weddings and holiday.

Below a cropped image: Magdalene Sibylle of Prussia (31 December 1586 – 12 February 1659) was an Electress of Saxony as the spouse of John George I, Elector of Saxony. i.0043, Photo from the Rüstkammer/SKD für die Ausstellung „Der frühe Vermeer“ Gemäldegalerie Dresden, 2010

History:

Deciphering fashions in the 17th century requires following a garment back to its place of origin. Then one can see it mature, spread and evolve into other styles. The Tabbaard got its start in Italy - likely Venetian - and is seen there by the third quarter of the 16th Century (about 1580s). The tabbaard, however, gets picked up by various nations though in differing styles. For France, it will morph from the Italian style to a bodice with a front sloping "swan" waist at the turn of the century. Then to a high-wider waist in the 1630s as can be seen with Magdalene Sibylle of Prussia gown pictured above; and a long more up-right torso for the rest of the century. The Images below are all Central European extant tabbaards with known owners. Note the waist line drops from the left to the right as the century moves forward.

Below cropped images: Left (Dated to 1635-1645) and Center (Possibly 1645) gowns once owned by Magdalene Sibylle of Prussia (31 December 1586 – 12 February 1659), Right tabbaard bodice in the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt Collection 1660.

The first two bodices are on display and are part of a show being held at the Dresden Rüstkammer museum in Germany. See link to the museum's site Scroll down to see VIDEO.

The Tabbaard in Holland:

The tabbaard is defined by Marieke de Winkel in her book Fashion and Fancy: Dress and the Meaning in Rembrandt's Paintings. It is a gown made up of a stiffen bodice that is laced up the back, it is not boned, but has a matching skirt. A petticoat is worn under the skirt. Fashion and Fancy includes a number of inventories and explanation of men and women's garments and accessories based on de Winkel's graduate thesis and an impressive number of primary sources.

In one of the inventories included in the book is that of a wealthy couple Captain Maerten Pietersez Dacey and his Widow Oopjen Coppit, November 1659. The inventory is massive and includes the following gowns:

In the bottom wardrobe

a plush tabbert of Oopjen Coppit

a "toers" tabbert of the same

a serge tabbert of the same

a red under pettcoat with passements

a green satin skirt of the same

a violet satin shirt of the same

an ash gray satin skirt

a green daily skirt

a small red under-petticoat

a white birds-eye skirt [petticoat]

When looking at Coppit's inventory we see a plush, "toers" and serge "tabbert". The plush is a velvet, the "toers" is a corded silk made in Belgium or Holland ( likely Leiden) woven in the Ottoman Empire fashion with blend of cashmere and silk; but sometimes with just silk. It is a slightly larger grain than modern silk fallie. (We will discuss corded silks in a later post.)

New Netherland and New York:

As we can see, both royal and wealthy merchant women of Europe are wearing the tabbaard. The images of the Electress's extant samples above were chosen in part because we know who owned them and when the she lived, with a death in 1659, making them easy to date and compare. In New Netherland and New York there is no royalty and it is not with the mega-merchants that we find three or four tabbaard per inventory; it is the growing middle class and frugal farmers that have acquired one tabbaard each. They are likely the wedding dresses that are later recycled into Holiday and special occasion wear. These wardrobes have another important outfit called the vlieger, which are more reserved in appearance and likely what was used for Sunday best. Though, due to the late date of these wardrobes it is also possible that these tabbaards were acquire to take the place of their vlieger even for Sunday best.

In an inventory from 1664, we see a fashionable couple with three little children sporting both vintage and the latest trends from Europe. They weren't living in London, or Amsterdam or Paris, but in a little town called Wildwijk on the Hudson River. Looking at the 1665 inventory of Rachel de la Montagne (d. 1664) and Gysbert van Imbroch (d. 1665), we are seeing the inventory of doctor from a small town. Prior to arriving in Wildwijk, Gysbert supplemented is income by winning the bid to perform the duties of selling testaments and bibles for two years in Manhattan. It seems that selling books becomes a on-going side job, as his inventory taken in Wiltwijk could fill a town library. It included a variety of books on literature, gardening, medical and school books for children. It is not unusual for people to pick up side jobs to make some extra income. Unfortunately, they died young leaving a 5, 3, and 1 year old; the children of which went to live with family. Interestingly, not only have their children and inventory survive them but so has their stone house which can be visited in the old section of what is today called Kingston, New York. Also, we can see that while Imbroch was Dutch, de la Montagne was French Huguenot.

In de la Montagne's wardrobe is a "tabbaard" (spelled in her inventory as "Tabbard") that could be worn with one of her three petticoats and a number of white or black hoods, two fans, handkerchiefs both round and square and even two cosmetics. She also had two cosmetics; one red and one black. Plus a few night time forehead bands that would be infused with oils intending to reduce the likelihood of wrinkles. The rest of her inventory is made up of jackets.

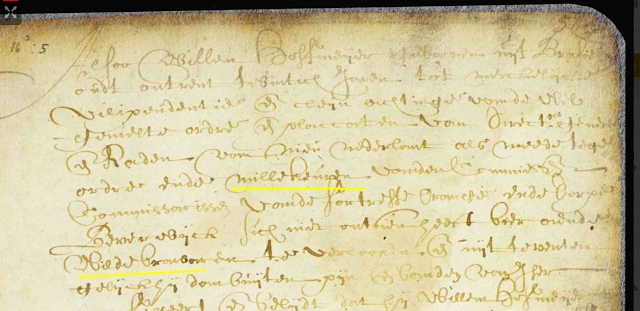

1665 inventory of Rachel de la Montagne (d. 1664) & Gysbert van Imbroch (d. 1665), Wiltwijk, NN

A black silk gross grain "Tabbert" with "sarcenet" under (a type of soft lining)

A colored gross grain petticoat with green lining

A colored changeable [silk] petticoat with green lining

A red scarlet petticoat

Inventories in New Netherland and New York tend to point out when a garment is scarlet, red, purple and black. This is in part due to the high cost of these dyes combined with the labor. When the item is simply stated to be "colored" the only option - in an effort to guess the color - is to note the other colors that were mentioned and know it was not one of those. Alternatively, if there is something notable for instance "changeable" silk or if it is lined the recorder will point this out. In the original translation of this inventory from the 1900s, the "A colored changeable petticoat with green lining" was originally translated as "reversible", but it is actually "changeable". Research such as that done by De Winkel in her book Fashion and Fancy has traced many of the 17th Century clothing terms for us.

The Tabbaard comes on the scene in an early form for the wealthy of Continental Europe in the late 1500s, remains a gown of choice throughout this time, then starts to spread from nobility and large merchants to the burghers (small traders) and crafts people by the 1650s. Rachael and Gysbert were married in 1657, and it is possible she brought this gown with her from her hometown of Albany, NY. Interestingly, both Rachael's tabbaard in New Netherland and Oopjen's tabbaard mentioned in the 1659 Holland inventory previously are both made of corded silk, or a corded cashmere-silk blend.

By the 1660s, the Tabbaard was accessible to well off farmers also. A second tabbaard is in a 1664 inventory from Fort Orange near Albany, the wardrobe of which had both vintage and modern clothing including; "1 tabbaard bodice [stored] in a piece of white cloth". It is possible that this bodice was a gross grain also as many other items including hoods and aprons were also made of gross grain, but may or may not be purse silk.

Below is a Tabbaart gown with matching bodice and skirt plus an under petticoat. This particular tabbaard would be very similar to the ones worn in the two 1660s inventories above. Also, over skirt were often sewn to the tabbaard.

Below self portrait, Zelfportret van Gesina, driekwart naar rechts, Gesina ter Borch, Joost Hermans Roldanus, 1661.

Here you can see both a family in formal tabbaard and the servants in more casual but also lovely tabbaard. Painting by Gillis van Tilborgh born 1625 Link.

Through each of these eras, the sleeves change to follow current trends while retaining the general silhouette, plus the bodice and the front princes seams on the torso. We can see the sleeve becoming longer. Many tabbaard in jacket form have attached sleeves whereas, the bodice versions or summer versions have attachable sleeves. Also, in the 1640s to 60s, it is a formal gown with matching bodice and skirt with under petticoat, it becomes more relaxed as a semi-formal and even casual wear in the 1660s and 70s.

By the third quarter (1670s), servants and laborers up-date their stays (a corset like garment) and jackets to look more like the tabbaard. The working class stays and jackets take on the princes-like seams and shape of the Tabbaard bodice but may or may not keep the sleeves. See Dordrechts Museum Link. for the image below. But simultaneously, for wealthier people the gown becomes formal again.

The 1664 Wiltwijk and Fort Orange inventories were not the only lists with a Tabbaard. Another can be found in the 1690s. A rather nice one appears in Lysbett van Eps's inventory who was a small trader-merchant; you may remember her as being the Albany shop keeper selling large qualities of Indigenous Leggings for adults and children.

Van Eps may have acquired her tabbaard when she made a trip to Amsterdam in the 1670s to purchase fabric for traded. While the one in the 1690s inventory has an unknown color it came with a detached skirt with both being made of fine "toers" corded silk. This is a fine grain fabric that has survived the centuries due to the quality. It is a silk that wares well, and from which modern bridal gown are be made. This is likely the Fort Orange tabbaard coming back into the formal-ware category again.

Re-Cap:

1659 Holland, Marchant: a plush tabbert, a "toers" tabbert, a serge tabbert

1664 Fort Orange, Farmer: 1 tabbaard bodice [stored] in a piece of white cloth

1664/65 Wiltwijk, Doctor's wife, book seller: A black silk gross grain "Tabbert" w/ sarcenet lining

1693 Fort Orange, Shop keeper: 1 ditto [toers] "tabbaart" "cijt"

One of the nice things about these examples, is that it leaves the door open to women from different economic backgrounds as having access to this type of gown. It is something that can be worn formally or semi-formal, in matching top and bottom or mixed and match. Interestingly, this garment continued to be used under English sovereignty. It is possible that the large merchants of the colony had more than one tabbaard, whereas we can see that famers, shop keepers, and professional's wives may of had only one.

The tabbaard will continue to live on from the 17th Century and into the 18th Century. Below Left to Right is a 1659, 1690 and then 1745 painting. The tabbaard is also called a camisole in German and is part of the court costume throughout this time frame. While the tabbaard will come in and out of fashion in France and England, it had become part of the wardrobe for Central Europe since the 1630s.

Below Image Cropping Left to Right: Left Jeanne Parmentier by Bartholomeus van der Helst, 1656 , LINK. , Center Eleonore Magdalene von Pfalz-Neuburg LINK. , Right Madame Henriette (Louis XV's daughter) playing the Viola da Gamba in Court dress by Jean-Marc Nattier (1685- 1766) LINK.

The tabbaard is not the only formal outfit that appears in inventories, however, it is the most fanciful or princes like. As we continue to explore we will see formal-ware was as important to the wardrobe as exotic and worldly robes from the east.

1664/65 Wiltwijk, Doctor's wife, book seller: A black silk gross grain "Tabbert" w/ sarcenet lining

1693 Fort Orange, Shop keeper: 1 ditto [toers] "tabbaart" "cijt"

One of the nice things about these examples, is that it leaves the door open to women from different economic backgrounds as having access to this type of gown. It is something that can be worn formally or semi-formal, in matching top and bottom or mixed and match. Interestingly, this garment continued to be used under English sovereignty. It is possible that the large merchants of the colony had more than one tabbaard, whereas we can see that famers, shop keepers, and professional's wives may of had only one.

The tabbaard will continue to live on from the 17th Century and into the 18th Century. Below Left to Right is a 1659, 1690 and then 1745 painting. The tabbaard is also called a camisole in German and is part of the court costume throughout this time frame. While the tabbaard will come in and out of fashion in France and England, it had become part of the wardrobe for Central Europe since the 1630s.

Below Image Cropping Left to Right: Left Jeanne Parmentier by Bartholomeus van der Helst, 1656 , LINK. , Center Eleonore Magdalene von Pfalz-Neuburg LINK. , Right Madame Henriette (Louis XV's daughter) playing the Viola da Gamba in Court dress by Jean-Marc Nattier (1685- 1766) LINK.

The tabbaard is not the only formal outfit that appears in inventories, however, it is the most fanciful or princes like. As we continue to explore we will see formal-ware was as important to the wardrobe as exotic and worldly robes from the east.