Leather breeches can be found in continental Europe and in England. So, it is not surprising to see them in New Netherland and later British New York. They are also readily found in New England and possibly New Sweden. This is great for reenactors who are looking for something different for their kits. Though, less so for vegetarians like me but the reality was that at the time, leather breeches were available and used. (I especially like the one's linked to below.)

From early in the 17th Century both New Netherland and New England had leather breeches in their inventories. However, from the sample in the database, they do not turn up in the same manor. In New Netherland, leather breeches are often listed as if an alternative to the cloth/textile choice, or simply on their own. This rule of thumb is flipped when it comes to New Sweden (Delaware) and also New England, where leather breeches are found often - but not always - in suit form. There are a couple references stating that in New Netherland and New Sweden breeches are made from elkskin as compared to buck or otter skin jackets.

Also, how one secures one's breeches to their body, may be somewhat different between New Netherland as a whole and New England. However, for this last point there is only a couple primary sources currently available that show the presents of of suspenders and girdles for men, so we cannot determine the frequency of use.

I couldn't fined a good image of 17c leather breeches; 18th Century leather breeches, Link.

From early in the 17th Century both New Netherland and New England had leather breeches in their inventories. However, from the sample in the database, they do not turn up in the same manor. In New Netherland, leather breeches are often listed as if an alternative to the cloth/textile choice, or simply on their own. This rule of thumb is flipped when it comes to New Sweden (Delaware) and also New England, where leather breeches are found often - but not always - in suit form. There are a couple references stating that in New Netherland and New Sweden breeches are made from elkskin as compared to buck or otter skin jackets.

Also, how one secures one's breeches to their body, may be somewhat different between New Netherland as a whole and New England. However, for this last point there is only a couple primary sources currently available that show the presents of of suspenders and girdles for men, so we cannot determine the frequency of use.

I couldn't fined a good image of 17c leather breeches; 18th Century leather breeches, Link.

Common Examples of leather breeches from New Netherland and New York:

1662 - Wiltwijck, Ulster Co., Wages earned by a young apprentice

four schepels of wheat and a pair of leather breeches

1664 - Brooklyn, New Netherland/New York, Upon a 14 year old's mother's death, the boy owned

a pair of leather breeches

1665 - Albany, New York, From the Church Deacons to Frans Coninck’s children

2 packages [one complete set or suit] of leather clothes, on which were used 7 deer skins

You probably noted a trend above. Children from about seven (7) years old through the teen years were likely to have leather breeches. Leather, along with Serge, were some of the most common textiles used for active kids.

New Netherland and New York's various records also show the use of leather breeches by adults. While breeches for women turn up more often in this colony than others, I have yet to find them in leather. But then again, leather breeches do not turn up in men's inventories at a high frequency either, but they are not unusual either. It is probable that this garment wore out quickly as it is a work horse for those in carpentry, masonry, etc. Also, while I have many farmer's inventories; I have but a few carpenter's, mason's, etc inventories.

On the 23rd of January 1642

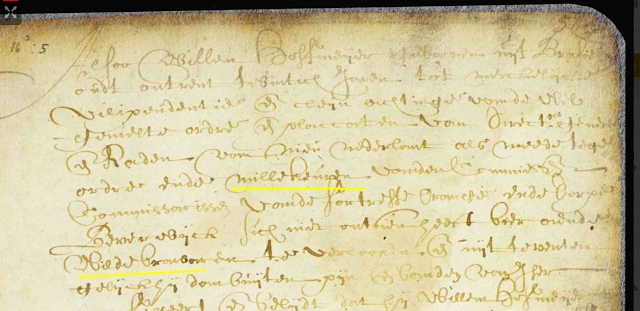

Gregorio Pieterse, plaintiff, vs. Tomas Coninck, defendant.

Plaintiff demands payment for an elk skin which cost him 8 gl [gilders].

Defendant answers that he warned the plaintiff that breeches were made of the elk skin. He is ordered to prove the same.

and

1666 - WIC Employee and Trader with the Native Americans, Fort Orange inventory:

[adult] a leather and a cloth breeches f 36.10.00 [no leather coats or jackets were included]

Primary and Secondary Sources for the leather breeches of New Sweden and later New Amstel:

I have seen a few references to the people of New Sweden (1638 to 1655, afterwards called New Amstel) wearing buckskin or elk breeches, but they are 19th or 20th Century sources. Also, the documents available currently are not turning up probate inventories to New Sweden outside of a few inventories where a Dutchmen is planning a trip. This said, items being sent to New Amstel are;

You probably noted a trend above. Children from about seven (7) years old through the teen years were likely to have leather breeches. Leather, along with Serge, were some of the most common textiles used for active kids.

New Netherland and New York's various records also show the use of leather breeches by adults. While breeches for women turn up more often in this colony than others, I have yet to find them in leather. But then again, leather breeches do not turn up in men's inventories at a high frequency either, but they are not unusual either. It is probable that this garment wore out quickly as it is a work horse for those in carpentry, masonry, etc. Also, while I have many farmer's inventories; I have but a few carpenter's, mason's, etc inventories.

On the 23rd of January 1642

Gregorio Pieterse, plaintiff, vs. Tomas Coninck, defendant.

Plaintiff demands payment for an elk skin which cost him 8 gl [gilders].

Defendant answers that he warned the plaintiff that breeches were made of the elk skin. He is ordered to prove the same.

and

1666 - WIC Employee and Trader with the Native Americans, Fort Orange inventory:

[adult] a leather and a cloth breeches f 36.10.00 [no leather coats or jackets were included]

Primary and Secondary Sources for the leather breeches of New Sweden and later New Amstel:

I have seen a few references to the people of New Sweden (1638 to 1655, afterwards called New Amstel) wearing buckskin or elk breeches, but they are 19th or 20th Century sources. Also, the documents available currently are not turning up probate inventories to New Sweden outside of a few inventories where a Dutchmen is planning a trip. This said, items being sent to New Amstel are;

1661

7 ells red duffle

1 anker anise & 20 ells red duffle

30 ells linen

10 ells linen

10 ells linen

1 pair of stockings

1 pair of stockings & 2 pairs of shoes

1 pair of shoes

There tends to be a distinct lack of clothing outside of stockings and shoes being sent to the New Amstel area from New Netherland. The above is a sampling for the year 1661, the records included additional anise, linen, red duffle plus items like Spanish wine as the year continues. Its possible they had a person sewing skins for jackets and breeches for the population. Many of the people located here were farmers. Further research is needed to uncover primary sources for this specific area.

One early 20th Century document gave the following referencing buckskin jackets and elk-skin breeches:

"Their dress wa chiefly of coarse woolen cloth, their shirts of linen, their stockings of felt, wool or linen, according to the season and the purse of the wearer... Leather, either tanned or cured in Indian fashion, was easier to procure and more durable to wear than woolen cloth, so coats made of leather, buckskin or otter skins, and elk-skin breeches were later commonly worn." - The Dutch and the Swedes on the Delaware 1609-64

These 19th and 20th sources may be referencing a 1749 interview of the "Oldest Swede on the Delaware, Nils Gustafson of Raccoon Creek". The interview occurred on the 16th of March 1749 old style. A man by the name of Peter Kalm did the interview of the 91 year old Gustafson who was born in America in 1658 to Swedish parents and is found in the book "Peter Kalm's Travels in North America".

"Before the English came to settle here, the Swedes could not get as many clothes as they needed, and were therefore obliged to get along as well as they could. The men wore waistcoats and breeches of skins.... The women were dressed in jackets and petticoats of skins."

From what I understand there are inventories from he late 17th Century from people who were Swedish and Nordic settlers. So, we will return to this topic and clothing in general for this region once enough inventories are secured.

The leather breeches of New England:

One early 20th Century document gave the following referencing buckskin jackets and elk-skin breeches:

"Their dress wa chiefly of coarse woolen cloth, their shirts of linen, their stockings of felt, wool or linen, according to the season and the purse of the wearer... Leather, either tanned or cured in Indian fashion, was easier to procure and more durable to wear than woolen cloth, so coats made of leather, buckskin or otter skins, and elk-skin breeches were later commonly worn." - The Dutch and the Swedes on the Delaware 1609-64

These 19th and 20th sources may be referencing a 1749 interview of the "Oldest Swede on the Delaware, Nils Gustafson of Raccoon Creek". The interview occurred on the 16th of March 1749 old style. A man by the name of Peter Kalm did the interview of the 91 year old Gustafson who was born in America in 1658 to Swedish parents and is found in the book "Peter Kalm's Travels in North America".

"Before the English came to settle here, the Swedes could not get as many clothes as they needed, and were therefore obliged to get along as well as they could. The men wore waistcoats and breeches of skins.... The women were dressed in jackets and petticoats of skins."

From what I understand there are inventories from he late 17th Century from people who were Swedish and Nordic settlers. So, we will return to this topic and clothing in general for this region once enough inventories are secured.

The leather breeches of New England:

The one off leather breeches in New Netherland and later New York are in contrast to the leather breeches in New England for the narrow time period of 1641 to 1661. Below are most of the accounts of leather garments from Essex Co., New England that mentioned leather breeches, jacket or suit. For New England reenactors suits of leather are a great option and possibly reflect the less urban and high number of farms and villages:

1641, Ipswich Town Records

1 pair of stirrup hose

1641, Ipswich Town Records

1 leather "dublet", 8s. 6d.

1 pr. leather stockings, 2s.

(Below are three different 1647 inventories)

1647, Essex Co., MA

a leather Suite, 1Li. 6s. 8d.

a leather Jacket, 4s.

1647, Essex Co., MA

one leather "sute" 1li.10s.

one leather jacket, 1li.,

1647, Essex Co. MA

one leather suit, 1li.6s.8d.

one leather "dublett", 14s.

1655, Essex Co. MA

one "sute" of leather, 18s.

1661, Salem

a leather Jacket, 4s.

Suspender and Girdle:

When looking to see how these leather breeches were held to the body, it is likely they were simply buttoned. However, both New Netherland in 1665 and New England in 1648 each have another way; leather suspenders and leather girdle respectively. These items turn up rarely, likely due to their repeated use which would cause a high level of wear and tear. But these inventories at least allow us to see they both existed.

In the New England none of the inventories use the term "belt" unless paired with a sword or similar weapon. "Girdle" is found in four inventories; 1 leather, 1 embroidered, and 2 silk. In New Netherland and later 17th Century New York girdle is used for 3 different silver girdles for women.

1665 - Surgeon, Wiltwijck, Ulster County, NewYork

a leather suspender

1648, Essex Co. MA

four Cushings & a leather girdle

The "one leather suspender" is likely, not that there were originally a pair of two separate straps, but likely the Dutch-German style of lederhosen suspender which is sewn into one piece. See the below etching called "Brandspuitenboek" printed in 1690 by Jan van der Heiden.

Below, Are those green fabric suspenders??? "Portrait of a Host by Peter Jakob Horemans 1765"

The use of leather breeches in British New York continue through the 18th Century. Below are a few examples.

1702 Merchant living in both New York City and Southhampton, New York

To 3 old “Lather” “Briches” 12

To 2 old “payre” of leather “Briches” & 2 old “wastcoats” 000:18:00

1774 Duchess Co., New York

Two Pair of Leather Breeches 1:0:0,

1641, Ipswich Town Records

1 pair of stirrup hose

1641, Ipswich Town Records

1 leather "dublet", 8s. 6d.

1 pr. leather stockings, 2s.

(Below are three different 1647 inventories)

1647, Essex Co., MA

a leather Suite, 1Li. 6s. 8d.

a leather Jacket, 4s.

1647, Essex Co., MA

one leather "sute" 1li.10s.

one leather jacket, 1li.,

1647, Essex Co. MA

one leather suit, 1li.6s.8d.

one leather "dublett", 14s.

1655, Essex Co. MA

one "sute" of leather, 18s.

1661, Salem

a leather Jacket, 4s.

Suspender and Girdle:

When looking to see how these leather breeches were held to the body, it is likely they were simply buttoned. However, both New Netherland in 1665 and New England in 1648 each have another way; leather suspenders and leather girdle respectively. These items turn up rarely, likely due to their repeated use which would cause a high level of wear and tear. But these inventories at least allow us to see they both existed.

In the New England none of the inventories use the term "belt" unless paired with a sword or similar weapon. "Girdle" is found in four inventories; 1 leather, 1 embroidered, and 2 silk. In New Netherland and later 17th Century New York girdle is used for 3 different silver girdles for women.

1665 - Surgeon, Wiltwijck, Ulster County, NewYork

a leather suspender

1648, Essex Co. MA

four Cushings & a leather girdle

The "one leather suspender" is likely, not that there were originally a pair of two separate straps, but likely the Dutch-German style of lederhosen suspender which is sewn into one piece. See the below etching called "Brandspuitenboek" printed in 1690 by Jan van der Heiden.

Below, Are those green fabric suspenders??? "Portrait of a Host by Peter Jakob Horemans 1765"

The use of leather breeches in British New York continue through the 18th Century. Below are a few examples.

1702 Merchant living in both New York City and Southhampton, New York

To 3 old “Lather” “Briches” 12

To 2 old “payre” of leather “Briches” & 2 old “wastcoats” 000:18:00

1774 Duchess Co., New York

Two Pair of Leather Breeches 1:0:0,

For the reenactor this is a great addition to a kit. Considering the high number of German, Dutch, Scandie and others; maybe we will be seeing some Leder Hosen with suspender style outfits at the 17th Century reenactments !