From the time of the first permanent European settlement in 1618 in Albany, New York to the seizure of Manhattan by the English in 1664 and then final transfer of sovereign control to the British in 1674, legal records were kept in Dutch. After 1674, all legal documents were mandated to be kept in English; many documents such as inventories, wills, letters and others continue to be kept in Dutch, and sometimes German and French. While I am not a language scholar, we can use primary sources to determine the meaning of labels and how they were applied to different people and groups. Translation dictionaries can often give us clues in how and when labels are utilized. Terms such as wilde, indian/indean, Japon and Turk are all terms that appear in 17th century books, letters, legal records and inventories.

Bear with me, we are going to cover a topic that can be political. I ask that we look at it so that we can understand what 17th century people specific to New Netherland and New York were trying to state, explain or record in early documents.

The savage pea plants of America ! :

The term "wilde" may seem like an easy translation but it is not accurate due to the Dutch not using the word wilde in the same way English use savage, though there is consistency with the French and German. For instance, the Dutch would say "wild beast" which in English one could say "wild beast" or "savage beats". But the Dutch also use "wilde" for "wilde apple blossoms" and "wilde pea plants of America". Whereas, in English we don't say, "savage apple blossoms" or the "savage pea plants of America". (What a crazy movie that would be.) The term "wilde" for the Dutch is not interpreted as savage; "wilde" is meant to be interpreted as simply existing outside of the urban and formal farming culture, or "natural, in nature, of nature".

Terminology: In the 1708 Groot Fransch en Nederduits woordenboek it states the following:

"Sauvage", adj. Feroce, qui n'est point apprivoisé. Wildt, wreedt, ongetemt.

Bete Sauvage. Een wildt beest. [ wild Beast ]

Pommier sauvage. Een wildt appelboom. [ wild apple bloom ]

Humeur Sauvage. Een mufien aart, een wildt inborst. [ a wild mood ]

This particular label is needed for interpreting court records such as the following. Note that the terms "natural" or "wilde" female and "black" female are used rather than "savage/sauvage", "Indian", "barbarous" or a variation on the N-word. (Side Note: This is not to say the N-word does not turn up regularly, it does appear often in different forms; but it is important for it to have its own post with attached primary sources.)

New Netherland Council Minutes 1638 - 1649, page 37:

Ulrich lupoldt fiscael....vs. Nicolaes Coorn Sargant....Bylen die he ende de soldaten waren Gedaen om hout te hacken, aende "wilden" voor zijn particulier te verruilen ende bevers tegens Sijn gedaenen eet in mijn coy heeft gehadt. ... Van gelijken tot verscheiden maelen "wildinnen" [wilde females] ende Swartinennen [Black females] geheele nachten by hem gedachte hebben geslapen, in mijn Bet, tor presentie van alle de Soldaten." Page 37 Link.

"Ulrich Iupoldt fiscal vs. Nicolas Coorn Sargant... who by reason of his office was in duty bound to set a good moral example to his soldiers, has notwithstanding has been guilty of bartering with the wilde for private gain, the axes which were given him and the soldiers to cut wood and contrary to his oath has hidden the beavers in his bunk. ... Likewise, the defendant has at divers times had wilde females and black [swart=black] females sleep entire nights with him in his bed, in the presence of all the soldiers."

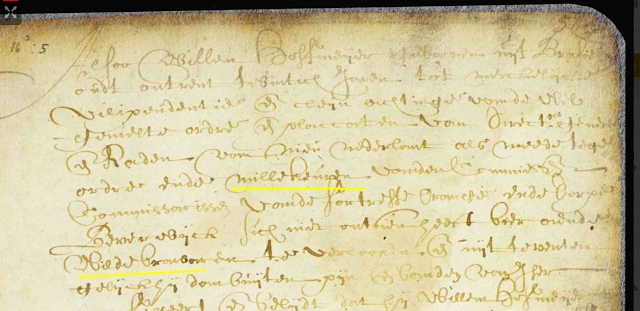

The below is a cropping of the 20th century original transcript (not original document from 1638) of the New Netherland Council Minutes 1638 - 1649, page 37 section 27. These documents are available for free on the New Netherland Institute's website.

Whereas, An Universal Etymological English Dictionary of 1731 states the following as the whole definition of "savage". The words savage and wild are separated. English Dictionary Link.

Savage, wild barbarous people who keep no fix'd habitation, have no religion, law or policy.

Here we get continuity, both colonial English and the Dutch use Barbarous (Dutch: Barbaar) for persons that appear to be a threat (though not to refer to themselves). When the Dutch wished to use a word closer to the English meaning of "savage" they used "barbarous", a barbarous people and may be associated with a person who purchases or drinks alcohol. This term has appeared occasionally in documents.

On October 1656 Willem Hoffmeyr from Brazil and living in Fort Orange, was being accused of selling beer to "wilde-indian" in the opening statement, with a more detailed account of "on the 22d, 23d, and 24th of July last past, with five half barrels of good and small beer mixed together, sailed up the river and sold and peddled the beer among the "wilde-barbar". The acusasaions continue with a reduction in the severity of "wilde-indian" and "wilde-babar" to "wilde" and the plural "wilden". - Fort Orange Council Minutes page 253 for the translated and also the original document from 1656 below. See the yellow underlines. Note that wilde is being used as the noun and Indian or barbarian as a descriptor. There are other nouns that are used in the same way such as Laken (a fulled twill woolen) vs. Serge Laken (a twilled woolen that is not fulled). The New Netherland Dutch tend to quantify many things in documents, so modifying the word wilde to meet the prosecutor's needs is not surprising.

The term Indian does not readily apply either, and is use rarely in Dutch and even German documents. This may be due to the Dutch being regularly exposed to products from and writings about the nation of India. Roughly 2/3rds of men and 1/3 of women in the Netherlands were literate. This too may of helped, as did the regular education of both boys and girls in lower schools.

In the 1655 Dutch book, Korte historian, ends jouraels aenteyckeninge, van verscheyden voyages in de vier deepen des wereldts-roune... the term "Indianen" is used to refer to the people of India, and rarely to the people of North America. The author having traveled to both regions and used separate terms to describe the people respectively. Likewise, we see this in inventories; Wilde (Native people), Indian/Indean (India), Japon (Japan) and Turks (Turkish). All these terms are use in inventories in America often in the same inventory to delineate different items and their respective place of origin and value.

Wilde, a People Recognized as a Nation:

One interesting practice was international treaties. The Dutch enter into treaties for trade and peace with various indigenous tribes. Not only did the Dutch recognize that the Native Americans were legally able to enter into and sign contracts, they were treated as a separate nation and could not be punished under Dutch laws. A Native American could bare witness in a court cases against a European on trial, but could not be prosecuted themselves. However, any incident performed by an Indigenous Person would be reported to the person's tribal leaders. One governor Keift even tried to tax Indigenous person, but this did not comply with general Dutch legal structures of separate nations under treaties. This recognition of separate people as citizens under their respective nations and subject to separate sets of laws also distinguishes the term "wilde" from savage. This acceptance tends to carry over to the English occupation from 1664 to their sovereign control in 1667, and until the second granting of sovereignty in 1674. As a whole, Both the Dutch and English seem to treat Native Americans as a people with culture and subject to respective legal systems during the 17th Century. More study is needed to determine when the turning point is but the purchasing of property from Native Americans continues though the whole of the 17th century, with Indigenous persons signing contracts and deeds at least until the year 1700.

Continued Use:

Inventories also shed light on another phenomena, the term wilde continues to be used along side "Indian" ten, twenty and thirty years after the British were granted sovereign control. Wilde disappears from court documents in 1674, but continues in inventories and letters into the 1690s.

Most interesting, people of Indigenous heritage are often referred to by name in Dutch and later New York era documents. Tribe names also make appearances, and the original Native American names for certain garments, material goods and other items create by indigenous persons are adopted by BOTH the Europen and British population. For instance, the term for a bag made by "wilde" is called "notassie" which is not a Dutch word but is regularly used by Europen people when referring to bags made by local Native Americans. Inventories in the Dutch from 1650 and in English from 1680s both use the term "notassie" (Dutch version) / "notase" (English version). I don't know which of the Indigenous languages this word comes from but the Mohawk and Lenape terms for bag are "kaiarowá" / "nikaiar" and "putalas" / "xesinutay" / "menutesa" respectively. It may be that the "me-nutesa" which is a handbag or purse is our "notase", as the two "notase" are described as fitting into a travel bag. It seems that the name of the handband or purse was a Lanepe word, adopted by the Dutch and then later by the English.

As we move forward through inventories whether under the Dutch or the English it is important to understand the different terms so to be able to appreciate the material goods in primary sources. The terms "wilde, barbarian, Indian, and savage" should be understood as accurately as possible and with understanding of the landscape it was used.

Was this helpful in understanding term "wilde" in 17th Century Dutch New Netherland and English New York ?

No comments:

Post a Comment